Works Cited | May 2019, Lincoln, NE

Cixous, Hélène.“The Laugh of the Medusa.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism (3rd edition). New York, W. W. Norton & Company, 2018.

I read this because I hadn’t yet, and because the article below by Laura García Moreno references it in relation to Pizarnik’s work. I did not end up using any of the text explicitly in the vignettes that make up “A Yellow Silence.”

Cusicanqui, Silvia Rivera. Sociologïa de la imagen. Buenos Aires, Tinta Límon, 2015.

Luis Othoniel Rosa refered me to this book and gave quote to help further my understanding of the problem of langauge, its limits, its inherent colonialism: “Hay en el colonialismo una función muy peculiar para las palabras: las palabras no designan, sino encubren, y esto es particularmente evidente en la fase republicana, cuando se tuvieron que adoptar ideologías igualitarias y al mismo tiempo escamotear los derechos ciudadanos a una mayoría de la población. De este modo, las palabras se convirtieron en un registro ficcional, plagado de eufemismos que velan la realidad en lugar de designarla” (175).

Inés, Sor Juana. “Answer by the poet to the most illustrious Sister Filotea de la Cruz,” (1691). Translated by William Little, 2008.

Federici, Silvia. Caliban and The Witch: Women, The Body, and Primitive Accumulation. Brooklyn, Autonomedia, 2004.

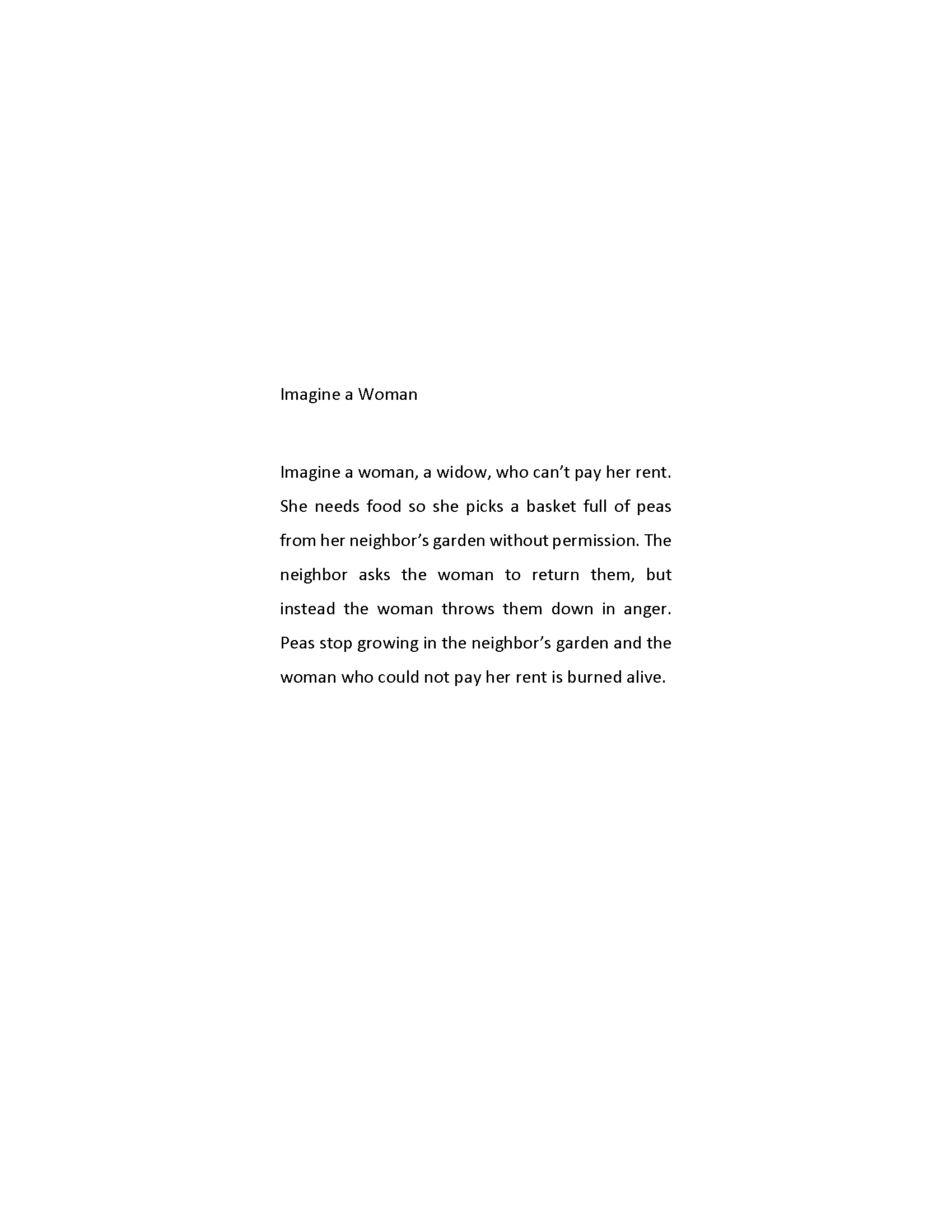

I explicitly used the preface, introduction, and the chapter “The Great Witch-Hunt in Europe” in this project. I was especially interested in how Federici answered the questions she poses at the end of the section from the witch-hunt chapter called “Witch Burning Times and the State Initiative.” She asks, “What fears instigated such concerted policy of genocide? Why was so much violence unleashed? And why were its primary targets women?” (169). Here are the quotes I gleaned from specifically:

“It should have also seemed significant that the witch-hunt occurred simultaneously with the colonization and extermination of the populations of the New World, the English enclosures, the beginning of the slave trade, the enactment of “bloody laws” against vagabonds and beggars…” (164).

“The witch-hunt deepened the divisions between women and men, teaching men to fear the power of women, and destroyed a universe of practices, beliefs, and social subjects who existence was incompatible with the capitalist work discipline, thus redefining the main elements of social reproduction” (165).

“The witch hunt was also the first persecution in Europe that made use of a multimedia propaganda to generate a mass psychosis among the population. Alerting the public to the dangers posed by the witches, through pamphlets publicizing the most famous trials and the details of their atrocious deeds, was one of the first tasks of the printing press. Artists were recruited to the task, among them the German Hans Baldung, to whom we owe the most damning portraits of witches” (168).

“The many ways in which the class struggle contributed to the making of an English witch are shown by the charges against Margaret Harkett, an old widow of sixty-five hanged in Tyburn in 1585: ‘She has a picked a basket of peas in the neighbors field without permission. Asked to return them she flung them down in anger; since then no pears would grow in the field…” (171).

Foster, David Williams. “The Representation of the Body in the Poetry of Alejandra Pizarnik.” Hispanic Review, summer, 1994, pp. 319-247.

Mackintosh, Fiona J and Karl Posso. “Árbol de Alejandra. Pizarnik Reassessed.” Colección Támesis, Serie A: Monografías, vol. 248, Rochester, Boydell & Brewer Ltd, 2007.

Moreno, Laura García. “Alejandra Pizarnik and the Inhospitality of Language: The Poet as Hostage.” Latin American Literary Review , vol. 24.48, 2001, pp. 67-93.

I got really stuck on part of the thesis of this article: “For if Pizarnik’s focus on the pain of a shattered psychic and linguistic identity conveys a transhistorical sense of time against which self and language wrestle with one another, her hesitation to assert an artistic authority or an “I” and the sense of loss and exile pervasive in her writing, I propose, are also symptomatic of: a) the oppressive dimension that a long-standing European convention of modern literature as a self-referential practice favoring text over author acquires for a female writer who felt deprived of language, self and place, b) an unassimilable post-war historical legacy, and c) a moment of national crisis in Argentina dating back to the forties and intensified from the sixties on, that goes beyond merely personal.

Pizarnik, Alejandra. Extracting the Stone of Madness, Translated by Yvette Siegert. New York, New Directions Books, 2018.

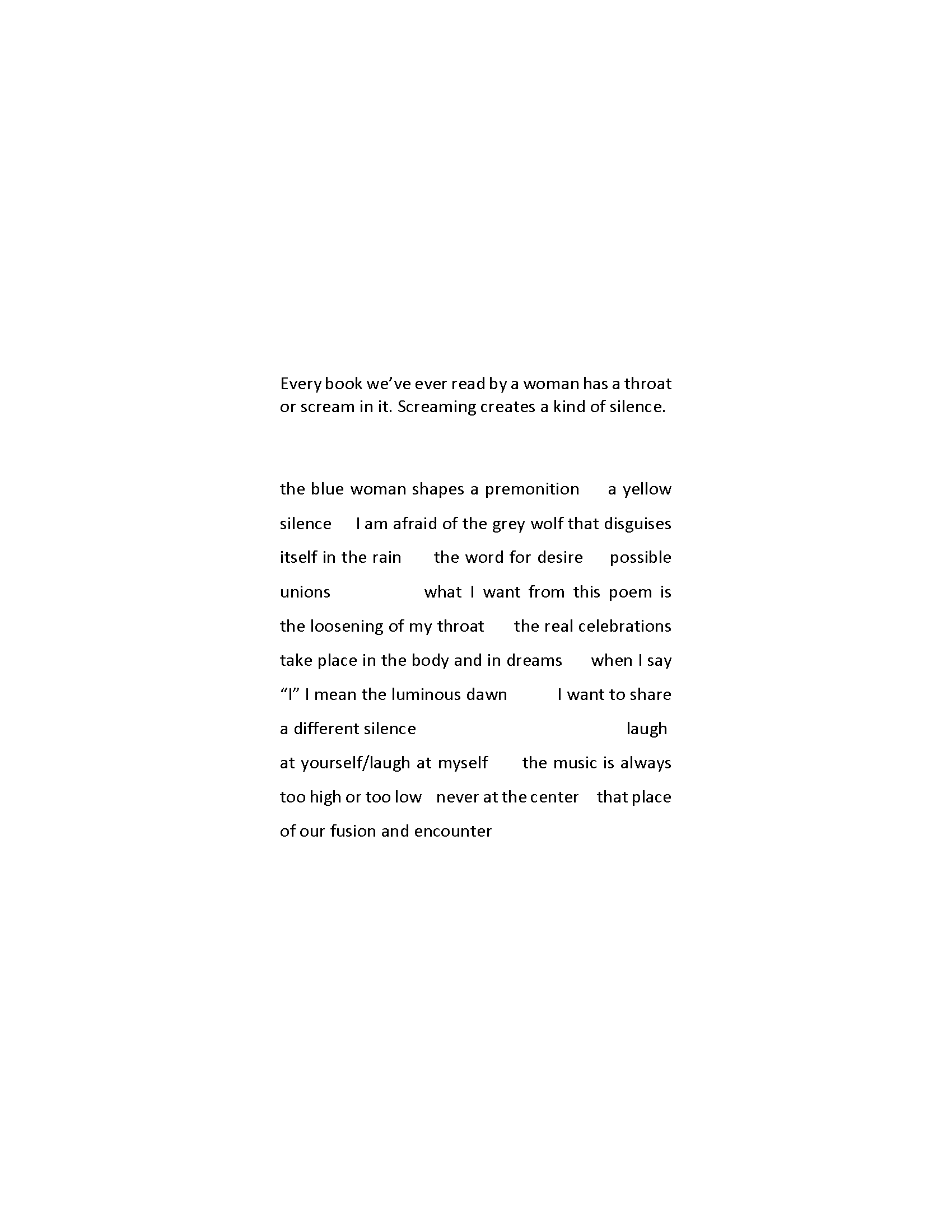

I made the mistake of not citing as I wrote the vignettes that make up “A Yellow Silence,” so it’s been hard to go back and trace what specifics came from where. I can say that I stole a lot and manipulated it on the level of grammar, point of view, and sometimes syntax. Here is a list of all the titles and pages numbers I definitely used:

Fragments for Subduing Silence, 53

Summer Goodbyes, 63

IV. (1964) Extracting the Stone of Madness, 71-79

A Nigh Shared in a Memory of Escape, 89

I. The Shapes of a Premonition, 95

Cornerstone, 97-99

The Word for Desire, 109

Possible Unions, 113

III. The Shapes of Absence, Of Things Unseen, 117

[…] Of the Silence, 151

On This Night, In This World, 191

For Janis Joplin, 225

Pizarnik, Alejandra. The Galloping Hours, Translated by Patricio Ferrari & Forrest Gander. New York, New Directions Books, 2018.

I stole from this whole book. It actually became the most crucial in the project, probably because I read it three times—once while zoning out while receiving acupuncture. That she wrote these poems in her “literary exile” does not seem insignificant. That she translated many of them when she returned to Argentina also does not seem insignificant. There is a translation thing happening in “A Yellow Silence.” I am trying to translate centuries of history into an artistic experience. I wrote in English, I stole from the English translations of Pizarnik. I would like to translate the work into Spanish, which would mean these fragments would have moved from French to Spanish to English then back Spanish at some point in their existence. That says something about the mutability and limits of language. Pages I know I for sure stole from include: 19, 23, 27, 33, 35, 43, 45, and 59.

Rich, Adrienne.The Dream of A Common Language: Poems 1974-1977. New York, W.W. Norton & Company, 2013.

I found it interesting to read Pizarnik alongside some of “confessional” poets of the US— Rich being at the tail end of that era. The psychosis of many of the white women writers like Plath, Sexton, and Levertov is not unlinked to Pizarnik’s work and life. The eroticism in Pizarnik mirrors that in Rich. I’ll do more research on this and write a paper about it one day.

Serra, Richard. Greenpoint. Outdoor steel installation, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Collection, 1988.

This sculpture was the physical impetus for this project. I walked through it daily for two years. This is a thing he said about his work. I found it via a random Google search and saved it: "Time and movement became really crucial to how I deal with what I deal with, not only sight and boundary but how one walks through a piece and what one feels and registers in terms of one's own body in relation to another body." I think it deepened my idea that “A Yellow Silence” should be experienced in small groups, not alone. Body to body.

Woolf, Virginia. The Waves. New York, Harcourt, Brace & World, 1959.

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own. New York, Harcourt, Brace & World, 1929.